A network of community health workers (CHWs) is responding to the humanitarian crisis in Central African Republic by delivering critical primary healthcare to vulnerable communities affected by ongoing conflict in the country.

Since 2008, this network of 450 CHWs has allowed The MENTOR Initiative to navigate violence and insecurity to reach communities in fragile areas with continuous healthcare support. Otherwise, these hard-to-reach communities could not access healthcare because of insecurity, poor roads, and cost of travel.

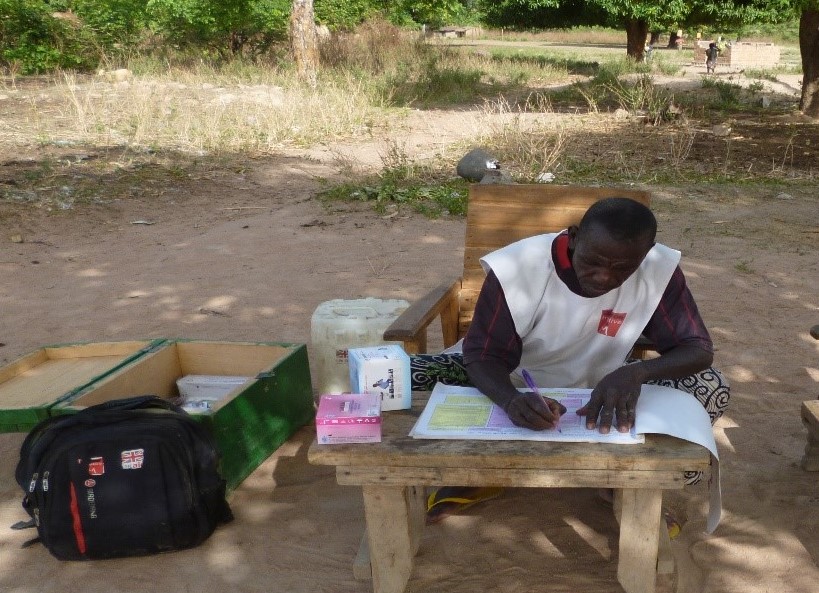

CHWs provide a range of healthcare services in communities, focussing on the three deadliest diseases – malaria, diarrhoea, and respiratory infections. They carry out screening for malnutrition, provide ante-natal services to pregnant women, and support mass distribution campaigns delivering deworming treatments and vitamin A.

CHWs also ensure communities know about vaccination campaigns and in some cases will support the delivery of them, for example vaccinations against polio. They deliver key messages about other campaigns or hygiene promotion – particularly important during the Covid-19 response.

CHWs identify patients who are severely ill and pay for them to be transported by local motorbike taxi to the nearest health facility or hospital. They are equipped to treat children with severe malaria symptoms and ensure they receive follow up care, significantly reducing deaths from severe malaria in these communities.

Recently, a few CHWs in CAR were interviewed as part of a study about their experiences delivering healthcare, and the challenges they face.

“During times of conflict when everyone goes to hide far away in the fields, I do the same with my community health worker documents and I treat patients. If we all hide in the bush and the community is trapped somewhere, I treat sick children under the trees.” – Mamadou*, community health worker.

“If people flee when there is war or people take refuge in a place, it’s up to me, the CHW, to seek them out to give them advice where they have gathered. If it’s in the bush, they must be sought out to give them advice on how to avoid illnesses by drinking clean water or sleeping under mosquito nets.” – Cyrille*, community health worker.

Providing health information and encouraging preventative behaviours is also an important part of their role. Odilon*, community health worker, said:

“Here are the benefits of the advice: there is a change in their behaviour. They didn’t see the importance of cleaning their houses, or good food preservation. But today, with the sensitisation [a process of raising awareness and understanding about an issue], when they hear talk of drugs, lots of people come for drugs for their children. Lots of pregnant women come too. That’s how I can say they’ve changed their behaviour.

Today, when you arrive in the village, you will see that they take care of their houses, they protect their drinking water, they sleep under mosquito nets. They have literally changed their habits after the sensitisation sessions.”

Last year (January 2022 to February 2023) 450 CHWs supported by MENTOR carried out over 118,700 consultations and diagnosed around 95,000 cases of malaria. The CHWs screened 83,622 children for malnutrition – diagnosing over 2,721 children with moderate acute malnutrition and 550 with severe acute malnutrition.

The programme is supported by UK Aid, UNICEF and USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (BHA).

*Names have been changed

About community-based healthcare in CAR

Community health workers are recruited directly from their own and host communities, ensuring they are trusted and established in their communities in a way that outsiders would not be. In cases of population displacement, the community health workers can move with their communities, and receive support and supplies from their supervisors in situ, or at an agreed safe location.

MENTOR also provides training, supplies and salary support for a number of roles within health facilities to improve referral level healthcare. This also enables a level of support for specific issues of concern such as gender-based violence.

We supply health facilities with appropriate medications and staff them sufficiently, without which health care would be completely inaccessible or virtually non-existent.

MENTOR’s community approach has been developed closely with the Ministry of Health and aligns with national health policy strategies in CAR.

Health challenges in Central African Republic

CAR remains among the most challenging places in the world in terms of provision of healthcare. A combination of poor living conditions, malnutrition and inadequate shelter means that disease spreads quickly and is often fatal, particularly in children.

The country’s health system is characterised by a scarcity of skilled health workers, a lack of essential drugs, and limited service delivery – including access to secondary health, sexual and reproductive health services. Young children and pregnant women are especially vulnerable to disease, illness and death in this setting, and mortality rates are unacceptably high.

A recent mortality survey* found the mortality rate in CAR is 5.6%, four times higher than the most recent UN prediction, and the highest national mortality rate in the world. The current social, political and economic indicators suggest that the humanitarian situation could worsen further in 2023.

The deteriorating nutrition status of many of the communities we serve is affecting immunity, which leads to increased susceptibility to diseases that are often life-threatening.

A 2023 nationwide cross-sectional survey found 83% of households report only eating one meal a day, including 73% of children. A third of households do not have access to sufficient, clean drinking water and 18% practice open defecation (up to 45% in Ouham Pendé subprefecture) because of the low country coverage of water and hygiene infrastructure.

A supported CHW network is an effective way of reaching highly vulnerable populations and providing a level of health care they would not otherwise have access to in an extremely volatile and unpredictable context.